Working for FEMA in the Aftermath of a Devastating Tornado, Part 2

The license plate says ‘Sweet Home Alabama,” which brings to mind beautiful, wooded mountains, coastal marshes, sultry nights and Reese Witherspoon. This image is in stark contrast with the damaged car tossed into a pile of downed trees, with no sight of the house where the car had been parked.

Actually, if you look closely at the debris skewed around the wreckage, you might see a table here, chair there, and pieces of insulation and metal roofing scattered around; so, I guess the house was there (everywhere) after all. I had stepped from a world of my imagination into a saddening reality. As I explained in the June issue of the ASHI Reporter, I was deployed to perform inspections for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) following the tornados this spring.

The damage that an F4 or F5 tornado can do, like the one that hit Rainsville, Alabama, doesn’t leave much intact or recognizable. Luckily, the lives of the occupants of this home fared better than the houses because everyone ran for cover as the storm of April 27 struck. Stories abound at every inspection about people who barely survived and those who didn’t. According to the reports on television, 238 people died that evening. I personally spoke with enough people at my FEMA inspections to know that the total easily could have been four or five times higher.

Photo above: Truck flipped over the road into the ditch in the Rainsville, Alabama, countryside.

Photo above: This house moved six feet off its foundation outside Henigar, Alabama.

When I left my home north of Dallas/Fort Worth, the devastation of Tuscaloosa and Cullman, Alabama, was the focus of all the newscasts. When I arrived in Birmingham, Alabama, and went through my orientation, I had no idea when or where I would be sent. It was only after a full day of travel, training and locating a motel to spend the night that I learned I was being sent to DeKalb County in far northeast Alabama. This is just a stone’s throw from Tennessee and Georgia, where damage also occurred. The agency assigns inspections by zip codes to FEMA inspectors in that area through a wireless modem to the inspector’s FEMA touchpad laptop.

A series of F5 tornados had cut a ½-mile wide swath about 25 miles long. Rainsville was located at the southwest starting point of this particular track of devastation. The destruction zone continued toward the Georgia border town of Trenton, just south of Chattanooga, Tennessee. This was my journey through the country roads of northeast Alabama. I quickly learned that a GPS has limits navigating back roads that were renamed sometime in the last few years. It was a challenging 11-day deployment.

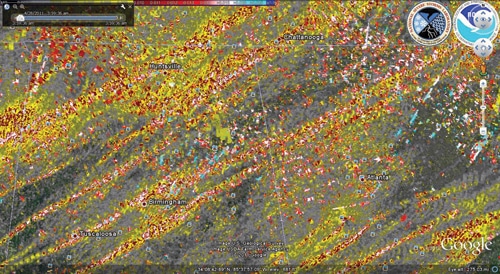

Above: A map of the storm tracks and dammage across Alabama in April 2011.

Rainsville, Alabama, was heavily hit as the storms traveled northeast from Tuscaloosa and Birmingham. Schools, churches, library, businesses and their new community center were badly damaged or destroyed. The F5 tornados then wound their way through the heavily populated areas to the northeast of Rainsville, causing death and destruction for an additional 25 miles. I started in this area and really saw the effects this event had on people’s lives. After inspecting a few lightly damaged properties, I hit the destruction zone and spent days winding through the complex of county roads accessing the rural neighborhoods outside Fort Payne. On one particular day, I inspected six homes and mobile homes that were totally destroyed, wondering at the miracle of how these people survived.

Photo above: The flattened remains of a home in Rainsville, Alabama.

One home was lifted off its pier-and-beam foundation and tossed 300 feet across a field. The occupant survived, after she was pulled from the rubble near her neighbor’s house and rushed to the hospital. Nearby, eight people had huddled together in the bathroom of a tiny house. A tree fell and crushed half of that house. This saved the eight occupants because the tree held the remaining half of the house from being blown away while everything else in sight was leveled.

All lived to tell the story. Truly, God was watching over a lot of people that day. The stories and sights would wake me at 3:30 a.m. as they rushed through my mind’s eye. Even long workdays of 14-15 hours couldn’t help me sleep a whole night until I got home and slept in the comfort of my own undamaged home. These articles are my attempt to process the experience.

Photo above: A house that survived in Trenton, Georgia.

Photo above: The apartment across the street in Trenton that didn’t survive the storm.

This was my second FEMA deployment. My first was to New Orleans and Baton Rouge for Hurricane Gustav; then, redeployment to Beaumont/Port Arthur Texas for Hurricane Ike. Each disaster has its own nature and characteristics. Hurricanes leave widespread damage like the Texas Gulf Coast that endured 100+ MPH winds for 14 hours and a storm surge that went inland 13 miles in some areas. The Alabama tornadoes had caused intense damage that was mainly confined to the storm tracks. Only 100 feet away from the devastation zone, homes had little or no damage. This is the nature of a tornado disaster.

The saving grace of this storm was that those unaffected by the storm (other than losing power for up to 11 days) were available to help neighbors who had lost everything. Volunteers stopped by at every inspection I performed on a destroyed property. They brought food and supplies; offered to help pick up things or cut the forest of downed trees that blocked every road, driveway and most houses. Tennessee is known as the Volunteer State and the care and support of its citizens was evident everywhere in Alabama. Employers, like Honda Motors, whose production lines where shut down by the loss of power and supplies, offered seven days of paid time off so employees could help the affected communities with the recovery. Crews of volunteers would come and cut hundreds of downed trees on a single road. That spirit permeated the communities and helped make this tragedy bearable to those so severely affected.

This was the first experience with FEMA for most people in Alabama. There were a lot of questions and even suspicion. It was up to me to put in perspective the IHP (Individual Homeowners Program) that I was working under. As taxpayers, we want the government to use our money wisely. As citizens of the United States, we don’t want people to be sleeping on the side of roads and under bridges when tragedy strikes. It is a fine balance that FEMA attempts to perform under difficult circumstances.

The governor of a state must declare an affected area a disaster and petition the president of the United States to declare the area a federal disaster. The process is designed to quickly and easily move federal government resources into the area. When a governor is slow to petition the federal government, as was the case with Katrina, people sit on roofs and live in football stadiums waiting for help. The petition to have an area declared a federal disaster requires the state to dedicate resources, so there are always some back-room discussions necessary to come to some agreement on getting the process rolling.

Once FEMA has an active declaration, it starts moving resources to the area. The 44 first step is establishing the logistical support necessary to coordinate the thousands of people involved. Food, water, housing, FEMA staff, inspectors and money start flowing immediately once a federal disaster is declared. FEMA guidelines already are in place, but may be tweaked slightly to address the circumstances of a particular disaster. Hurricanes, tornadoes, wildfires and floods all have different characteristics and needs. Everyone needs to be on the same page and focused on the needs of a specific disaster. The federal response includes money for temporary housing, immediate needs and cleanup. The IHP is just one part of that response, but money flows to the state, counties and individuals to help with the cleanup and recovery.

Homeowners insurance is designed to replace those things damaged or lost. FEMA and the U.S. government cannot afford to insure citizens’ property, so many are disappointed with the federal funds provided after a disaster. The IHP program is designed to provide immediate assistance to get someone who has lost everything back to a subsistence level and out of a tent. Temporary housing, a bed, table and chairs and a few appliances so families can cook and clean their clothes is the bulk of where the FEMA money goes. For someone who loses everything, an upper-end payment of perhaps $25,000 could not even start to replace what is lost.

The assistance is intended to help someone start over.

FEMA inspections are not big profit centers to the typical home inspector. A full-time FEMA inspector could make a decent living, but experiencing such destruction on an everyday basis is pretty gritty work (to me, anyway). But ,there may be a time and place for them in your inspection profile. Every time a federal disaster comes to your hometown, there will be a dramatic effect on the volume of your home inspection business. Home inspectors in La Butte or Morgan City, Louisiana, will not be able to work for months or longer as the Mississippi river is rerouted through their towns, causing flooding possibly 25 feet deep. Home inspectors in Raleigh, North Carolina; Galveston, Texas, or Tuscaloosa, Alabama, will feel the effects for months or years on their businesses. Joplin, Missouri, was hit a few days before I finished this article. Forest fires in San Diego are another recent disaster. Flooding along the Mississippi in Memphis will affect part of that market. We are not even talking about the 2011 hurricane season, which started on June 1. The nature of our world today appears to be that disasters can happen almost anywhere in North America.

This exact discussion took place at the January 2006 ASHI Board meeting in Ft. Lauderdale, when InspectionWorld conference hotels were damaged by the 28th hurricane of the 2005 season. The discussion centered on the income potential and effects natural disasters can have on ASHI members’ businesses if a disaster comes to their hometowns. With a little preparation, ASHI members may be able to use this program to provide business income when tragedy strikes. It could make the difference of whether or not you stay in business. FEMA training is free and accepted by ASHI and many regulated states for continuing education credits. Some ASHI chapters charge a fee to pick up the expenses associated with sponsoring these classes. If you are interested, you can go to www.PaRRInspections.com and click on the training links at the top of the page for more information.

As an ASHI member and former Board member, I ask all ASHI members to consider doing three simple things to help people affected by these tragedies.

1. Give money to the Red Cross today.

$10, $20, $50 or whatever you can afford. It is onsite at all U.S. disasters, providing food and assistance. You will never know how much they do. They provide hot food to affected individuals and the army of volunteers who are there to help, as well as check up on people who may have physical challenges because of age or infirmity. The Red Cross was there for those affected yesterday, today, and we all need to help it be there tomorrow. You may need its help one day.

2. Change the information you provide your homebuyer clients.

They are moving into a new property and need to know safe areas in their homes for emergencies, evacuation plans for fires and other contingencies related to their safety. You may be the only knowledgeable inspector to look at that property for years to come. Information necessary to survive a disaster is needed before the actual event.

3. Seriously consider becoming a FEMA inspector with either PaRR or Parson Brinkerhoff.

They are the two current FEMA contractors. Once trained, you can pick and choose what disasters you are willing and able to participate in via their online websites. As home inspectors, we have a unique skill set that makes this a natural extension of our profession. After Hurricane Katrina, ASHI members were trying to get involved with FEMA inspections in their devastated markets of New Orleans and Baton Rouge. After the disaster, it is too late to get your training and get set up in the FEMA system. Getting your training today is how you prepare today. Then you can decide tomorrow whether your business can switch gears to provide FEMA inspections if your market slows down or disaster comes to your town. You control your time and planning. If you chose to be deployed, they want 100 percent of your time and attention during the deployment.

The typical FEMA deployment is 10 days. I was on the Gulf Coast for 45 days in 2008 and 11 days in Alabama last month. I look at it like a Peace Corps experience, where I get to sleep in motels and eat out every day. It is tough emotionally, so this isn’t a vacation. It is not wildly profitable, like a good home inspection business that is really cracking, but it can pay the bills and keep the doors open when things slow down. Consider signing up and giving it a try.

I hope these articles have helped you understand the role of a FEMA inspector in a disaster and that you will sign up for a class today. You may choose to never be deployed, but information and knowledge are powerful things and create options in your business. Wouldn’t it be great if the FEMA contractors could turn to ASHI members as a ready pool of experienced and qualified inspectors to meet the nation’s needs in a time of tragedy?

———————————————————————–

Tips to make your FEMA experience more pleasant and profitable

• I performed 204 inspections on my first 45-day deployment (4.5 inspections/day average) and 75 inspections in 11 days in Alabama (6.8 inspections/day average). The faster you can perform the inspections, the more you get paid. Operating in the black makes any experience more pleasant. Learn the FEMA guidelines for your disaster.

• I drove 1,800 miles in 11 days after flying into and out of Birmingham. Your expenses to and from the disaster are picked up by the FEMA contractor. I rented a compact car in Birmingham that got 31 mpg for about $400 for two weeks. I drove my own car (21mpg) about 3,000 miles on my first deployment in Texas and had to pay for an A/C compressor. The rental car is the way to go.

• Keep your motel stay dates on a tight reign. FEMA inspectors are moved regularly and motel availability sometimes is hard to find. You can monitor your inspections on your computer and when you start running low, it may be an indication that you are going to work another (additional?) area. If your drive time to the new area is too long, then it is time to relocate.

• You need to take care of yourself while in the field. Exercise daily to relieve the stress. An early-morning walk worked best for me. Eat a good breakfast, carry some snacks and eat dinner early in the evening. If you eat late, you won’t sleep as well. Use your phone to talk to friends and family while you are on the road. You have to stay grounded with all the sorrow that you will see and hear.

• Pick up a new cellphone number ($10/month) for your deployment and change your plan to the highest minute plan you can get. Make the changes over the phone with your provider, because the large-volume minutes plan may not be viewable from the phone providers’ website. Get a Blue Tooth earpiece for your cellphone. Hopefully, you aren’t dialing out while driving; however, people will be returning your calls and inevitably you will be driving when they call. Touch the earpiece to make the connection, and you can set up an inspection time and date in just a few seconds because you already have their contact and address information. You can jot down the information when you stop or pull over.

• Learn your area when you arrive. Where is the local police station or fire department? You may need access to their maps to find addresses. The Rainsville police station made a copy of its map for me, and I could go anywhere in the area by a backup route. In another town, I probably went to the police station about six times a day to use its wall map. It was kind of funny (in a sick way) that my GPS always could identify where I was when I left an inspection, but never could navigate to that address from my last location.

———————————————————————–

To Read the Full Article

ASHI offers its members unparalleled resources to advance their careers. ASHI offers training for inspectors at all levels of knowledge and experience, including resources about all major home systems. Members benefit from a vast network of experienced professionals, providing a community for mentorship and knowledge sharing..

In this Issue

FIND A HOME

INSPECTOR

Professional Networking

Grow your professional network, find a mentor, network with the best, and best part of the community that’s making home inspection better every day.